Birth Injuries

If your baby had a limp arm(s) immediately after birth, they may have what is called a Brachial Plexus Birth Injury (BPBI). Other names for this condition are Erb’s palsy, obstetrical brachial plexus injury (OBPI), brachial plexus birth palsy (BPBP), and several other similar variations. Your doctor may have told it would resolve on its own, and many do, but you should still have your child examined by a BPBI specialist ASAP. If the injury is severe enough to require intervention, the timing of treatment is critical. Use our medical directory to find a specialist near you.

The next thing you should understand is that your baby’s injury is NOT your fault. Though there are some known risk factors and interventions that can be used to reduce the risk of BPBI, not all injuries are preventable. While your child gets the help they need, make sure to address YOUR OWN needs. This might mean joining an online support group or talking to a therapist. How you cope with your child’s injury will impact how they cope with it as they get older.

Additional Pages: About Traumatic Injuries FAQs Terms to Know Find Support

ⓘ BPBI Facts

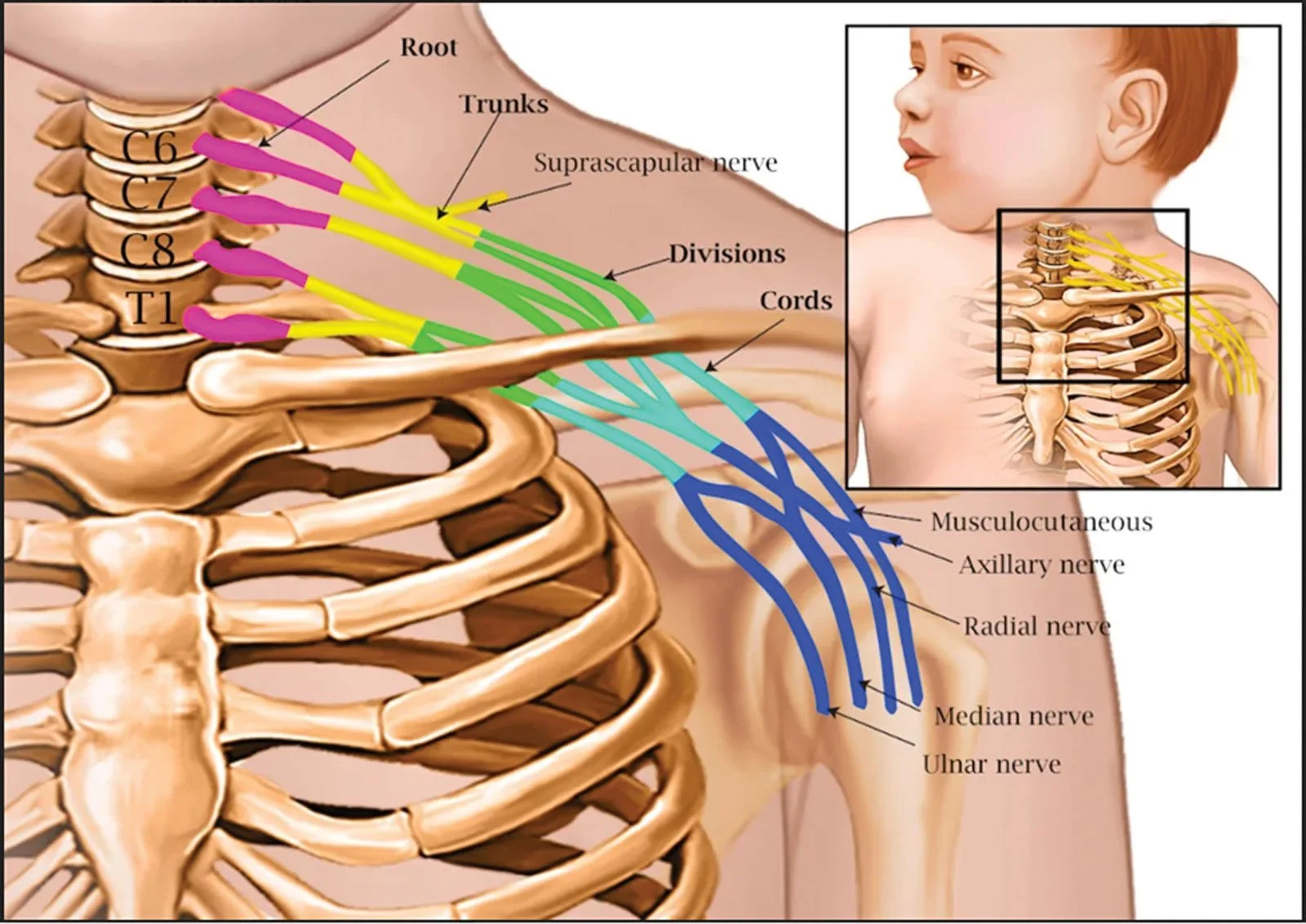

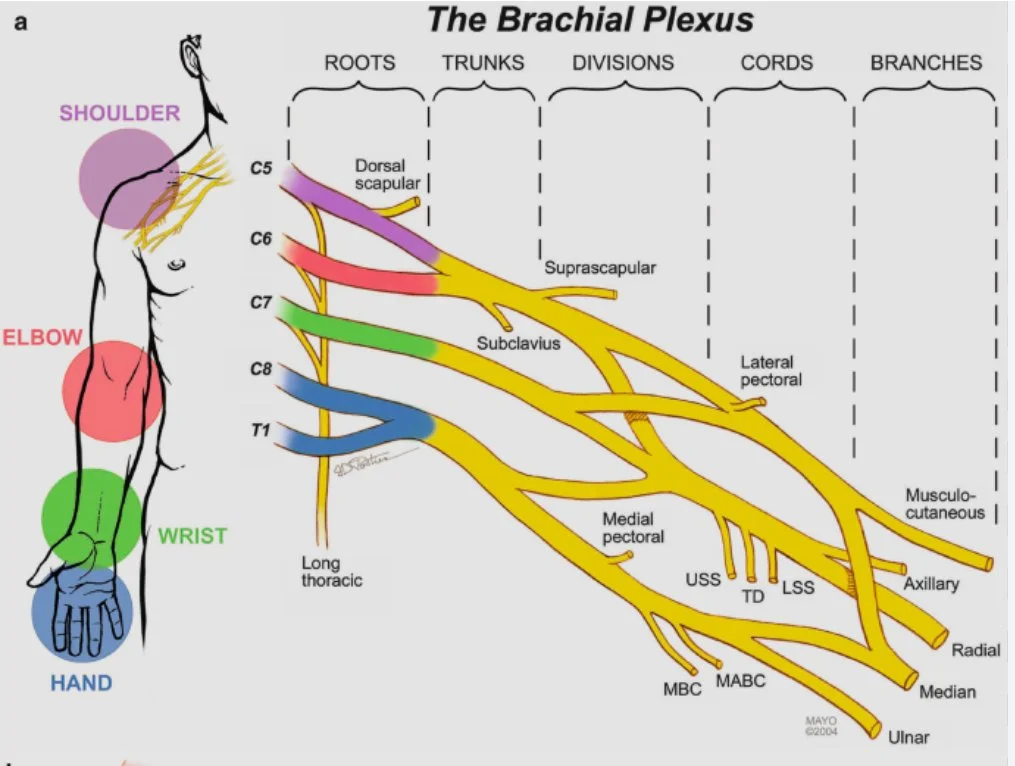

The brachial plexus is the bundle of nerves that exits the spinal cord near the neck and transports signals between the shoulder, arm and hand and the brain. Everyone has two brachial plexuses, one on each side of the neck, though it’s less common to injure both. The nerves exit the spine at the C5, C6, C7, C8, and T1 vertebrae.

A brachial plexus injury is the name for damage to the nerves within the brachial plexus, most commonly due to the nerves being overstretched or torn. While this can happen to anyone, it is unfortunately a fairly common occurrence during the birthing process. An injury caused during birth is known specifically as a brachial plexus birth injury (BPBI), while an injury caused at any other point in life is known as a traumatic brachial plexus injury (TBPI).

Image Credit: Dr. Koehler and Dr. Hasbani

Used with permission of Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. All rights reserved.

-

There is much controversy in the obstetrical field regarding causation. Simply put, the overwhelming evidence is that the delivering practitioner applies too much traction (pulls too hard) on the baby's head and/or uses contraindicated procedures while trying to dislodge the baby’s shoulders (shoulder dystocia) from behind the pelvic rim or from the bony sacral promontory (tail bone) while the woman is usually lying on her back and/or sitting on her tail bone.

In doing so, the nerves that innervate the shoulder, arm, wrist and/or hand can be severely damaged, resulting in partial to complete paralysis. Sometimes the force is so great that the nerves are actually pulled completely out of the spinal cord-reducing most possibilities of any useful function of the arm, and necessitating numerous surgical interventions in an attempt to gain even the slightest function.

Also, the nerve to the eye may be damaged, resulting in Horner’s Syndrome. In severe cases, the nerve to the diaphragm (phrenic nerve) may also be injured.

Shoulder dystocia is described as an obstetric emergency involving the lack of rapid, spontaneous delivery of the anterior shoulder of the fetus. The accepted proposal is that the shoulder gets lodged against the mother's pelvis symphysis (Inlet), although there is evidence to suggest that it can be a pelvic outlet phenomenon -a proposal that could support either shoulder being impacted. If it is a pelvic outlet issue, then either shoulder could be damaged from the traction, whether it be upward or downward traction that is applied. Rotational torque on the baby's head must be avoided during any manual manipulations to free the shoulders.

BPBI statistics vary widely, but the general consensus is that BPBIs occur in 2-5 out of 1000 births, and an estimated 30% have permanent complications.

-

Both birth and traumatic brachial plexus injuries can be classified using the same terms. Injuries can range from mild and temporary to complete severing of the nerve(s). In addition, the treatment and prognosis of a BPI depend directly on the extent of injury. Here are different terms used to describe the extent of a brachial plexus injury:

Neuropraxia (stretch) – when the nerves are stretched beyond their elasticity, some individual nerve fibers may be damaged, but the nerve as a whole remains intact. Some mild injuries are temporary and heal completely on their own. In other cases, as the damaged nerve heals a neuroma (scar tissue that has grown around the injury) may form, limiting nerve function.

Neuritis – inflammation of a nerve which can cause temporary or permanent changes in motion and sensation

Rupture – the nerve is torn completely, but not where it attaches to the spine. Surgery must be performed to save the nerve and restore function.

Avulsion – the nerve roots are torn from the spine. Avulsed nerves cannot be repaired as there is currently no way to reattach the nerve roots to the spinal cord.

-

Signs and symptoms of a brachial plexus injury include:

Weakness or not being able to use muscles of the shoulder, arm, and/or hand

Numbness or changes in feeling in the shoulder, arm and/or hand

Intense pain, often described as an electric shock or burning, that shoots down the arm (it is unclear if this pain occurs in infants, but it is very common in people who are injured later in life).

-

Diagnosis

Brachial plexus injuries need referral to a specialist as soon as possible upon detection. Clinical evaluation utilizing a combination of some or all of the following is used to determine the type and extent of injury:

Looking for sensory and motor changes in the affected limb with a physical exam

EMG (electromyogram) and/or Nerve Conduction Studies to determine the presence of nerve signals in the arm

MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scan to visual the nerves

Possibly CT Myelogram where contrast dye is injected into the spine and scanned to see if there is leakage from the spine or other indicators of damage.

Surgical exploration may be scheduled to physically examine the extent of injury.

Treatment Options

Non-surgical treatments are typically used for more mild injuries or as a supplement to surgery in more severe injuries.

Physical and/or occupation therapy is critical to maintaining range of motion while the nerves are healing, and help retrain muscles after surgical procedures

Medications can help manage symptoms, specifically pain, as needed

Surgical Procedures

-

Primary (nerve) procedures: Nerve injuries involving complete ruptures or avulsions require surgery in order to see improvement. The type of nerve surgery depends on the extent of the injury. When nerves are repaired, transferred, or grafted, the end of the nerve closer to the hand will not pick up and transfer the signal, but instead acts as a conduit for the upper portion of the nerve to regenerate through. This means that no signal will be able to reach the muscles until the nerve has entirely regrown from the point of injury to the muscle. The regeneration of damaged nerves is slow, about 1 inch or 3 centimeters a month. After nerve surgery, the recovery time frame is months to possibly years, although denervated paralyzed muscle tissue will atrophy and may not be receptive to nerve impulses after a period of time. It should be emphasized that just as the many possible complex variations of the injury occur, so does the rate and extent of recovery for each individual patient. As a general rule the smaller fine control muscles in the hand are in the most danger of being lost. Therefore, by the time any nerve recovery reaches the patient’s hand, atrophy may have resulted in lost function. Some injuries unfortunately do not respond to treatment and are so severe that they are permanent.

Neurectomy/neurotomy – this procedure is used to cut away damaged nerves either for pain relief or in preparation for further surgery

Nerve repair - this may be attempted in the case of more severe stretch injuries or ruptures of a nerve where the two ends of the existing nerve can be reconnected.

Nerve graft - nerves that were torn peripherally (not at the spinal cord) may benefit from nerve graft surgery (typically at 3 to 6 months post trauma) if the two ends of the nerve are no longer close enough to reattach, with the donor nerve being taken from the patient’s leg or other possible site and grafted in place of the damaged section of the brachial plexus nerve(s).

Nerve transfer - A functioning, but less important or extra nerve (such as intercostal nerve) is used to innervate the muscles by making one cut and attaching the portion of the sacrificed nerve that is still connected to the spine to the muscles that need to be innervated.

Musculoskeletal procedures: Besides the nerve grafting and scar tissue removal surgeries available as a possible option, there are other surgical techniques which can be utilized long after the initial period of injury. These include:

Tendon transfer - similar to a nerve transfer, tendon transfers will cut the tendon from when it connects to the bone and move it to another part of the bone so that the muscle can help move the arm in a different direction than it originally did. One example would be moving the tendon for the latissimus dorsi to the shoulder to help with rotation rather than pulling the arm in to the side.

Tendon release - if a contracture occurs, a tendon release may be performed to lengthen the tendon and increase range of motion.

Free muscle transfer - if a muscle has not received signal for too long, it will lose its ability to regain function, even if the nerve is repaired. In this case, a full muscle (usually from the leg) is moved to the arm to perform the function that was lost.

ⓘ For Parents

-

First and foremost, your child's injury is not your fault!

Obtaining a confirmed diagnosis in the first few weeks or days from your pediatrician or neonatologist is critical. Most parents report being told, “it’s a stinger” and/or “this will resolve in a few days/weeks” after their child’s injury. While this certainly can be the case with some babies, do not wait to ‘see’ if their arm will get better on its own over time as time is of the essence with nerve injuries! When it comes to nerve injuries, timing for intervention is critical and you are your child's best advocate.

Even though all nerves initially develop the same in utero, each child’s recovery, lack of recovery as well as course of treatment can vary greatly from another’s similar situation. There is no “one size fits all” for this injury therefore having your child be evaluated and treated by a BPI specialist and team is in your child’s best interest.

Birth-1 month of life

Speak with your pediatrician, neonatologist or whoever is evaluating your child initially as well as whoever will be following them once they are discharged from their place of delivery (hospital, birthing center, etc) as soon as you become aware of or have concerns regarding a difference in your child's arm movement, strength and/or function. You should INSIST on a referral to a BPI specialist/team right away and not wait for the first 3 months to pass. Most BPI specialists/teams wish to thoroughly evaluate a child within the first few weeks so the best plan of care can be developed based on your individual child’s injury and needs.

Before discharge, request an x-ray of your child’s clavicles and humerus (upper arm bone) to rule out fracture or break as this can occur during a difficult birth as well. If there is a fracture/break in a bone, this does not rule out a BPI simultaneously being present

Questions to ask medical team/therapists:

Request a referral to a BPI specialist/team as soon as possible

How should I hold my child? (It is generally recommended to always know where arm is, place the arm across baby’s chest/stomach and hold as you would any other child)

Do I need to place my child’s arm in any special way when holding, breastfeeding, placing in a carseat, etc? (It is generally recommended to always lay the injured arm across the chest/abdomen so it doesn’t accidentally get caught/tucked behind the child. When in a car seat/swing, you can roll up a receiving blanket and tuck under the arm/elbow area to support the arm as well so it doesn’t fall behind the child as they wiggle.)

Should we be doing any stretching or range of motion exercises? If so, what specifically and how often? Will I cause my baby pain doing this?

How do I find a local therapist (PT/OT) to show me how to start doing these gentle stretching exercises?

Is my child in pain? Will I cause my child pain by touching him/her or doing the prescribed stretches/exercises? (Routine touching and care of your child should not cause pain unless there is a fracture/break in a bone)

How do I dress/undress my child? (Putting the injured arm into a shirt/dress/jacket first, and removing the injured arm last is the standard.)

Request a referral to a children’s brachial plexus clinic (**see provider directory) ASAP. The current recommendation by BPI specialists/teams is to evaluate the injured child as soon as possible after birth to best assist in developing the best plan of care for the individual child.”

Request a referral to a state funded program to assist with Physical Therapy (PT) and/or Occupational Therapy (OT) right away as it can take weeks to obtain an initial evaluation by state funded programs. This is not an income-based program but rather a diagnosis-based need program that can provide these services to your child, sometimes right in your home depending on the evaluation and services available in your state. It may be called something different in the state you live in but some examples of names are below:

Birth to 3 years program

Early Intervention program

**As your child ages and their normal development progresses, their stretches/range of motion exercises will also change. Continuously ask your child's MD/clinic/therapists about what you can do. Request a referral to a Physical Therapist (PT) and/or Occupational Therapist (OT), preferably with experience with this diagnosis.

1-3 months

Your child should have already been evaluated by a BPI specialist/team at this point and may have had more than one appointment with that team so far. If not, request that referral or call a BPI specialist/team yourself to set up that initial appointment.

If you have not had a referral to a Physical Therapist (PT) and/or Occupational Therapist (OT) then request one from either your pediatrician or BPI specialist/team or both. A PT/OT can and should guide you on gentle range of motion (ROM) exercises. You should be continuing these gentle ROM exercises as directed.

If you have not had a referral to your state funded program to assist with PT/OT services (see above) then request this now as it can take weeks to obtain an initial evaluation

Questions to ask medical team/therapists:

Request referral to a BPI specialist/team if not already done

How do I find a local therapist (PT/OT)?

Can you assist me in making a referral to my state funded program to assist with PT/OT services?

What milestones should I be looking for my child to reach at this time?

3 month-6 months

Depending on severity of injury your child may be recommended for surgery at this age.

Questions to ask medical team/therapists:

How can I set up my babies toys, activity mat to encourage eye tracking and movement to their injured side?

What milestones should my baby be achieving now (with special attention to those requiring the use of both arms such as rolling over, stabilizing while attempting to sit in tripod pose, hand to mouth movement, grasping toys)

How often should I be following up with their Brachial Plexus team?

Will my child need surgical intervention?

What type of surgeries do babies with this injury need?

What type of therapies should we be doing and how often?

If you don’t have one already, ask How do I find a local therapist (PT/OT)?

6 months-12 months

Your child may be recommended for surgery at this age.

Questions to ask medical team/therapists:

What milestones should my child be reaching now?

How will my child be able to crawl or how can I encourage my child to crawl (some children skip this phase or do a modified crawl so PT/OT can assist with activities to encourage crawling motion)

Should we encourage crawling or go straight to walking?

How can we encourage her to use her injured arm during play, eating, etc?

How can we use toys/mirrors to facilitate increased use of the injured arm?

12 months-24 months

Your child may be recommended for surgery at this age.

Questions to ask medical team/therapists:

What milestones should my child be reaching now?

How can we help our child walk due to difficulties with balancing?

Our child falls over and is unable to use injured arm to stop their fall…what can we do to assist with this protective reflex?

Should we still be doing stretching/range of motion exercises?

My child is starting to resist their stretching….how can we incorporate these during play? (Your PT/OT can assist here)

How do we explain our child’s injury and needs to preschool or daycare workers?

How can Early Intervention (or other state funded programs) assist in the pre-school setting?

24 months-36 months

Questions to ask medical team/therapists:

Should we allow our child to participate in activities “other” kids do? (trampoline parks, playgrounds, etc)

How can we continue to incorporate stretching, range of motion exercises now that our child is more independent?

What types of toys/activities can be helpful to encourage movement/use of the injured arm?

How can I teach my child to dress or undress themselves with limited use of one arm?

How can Early Intervention (or other state funded programs) assist in the pre-school setting?

36 months to early school age

Questions to ask medical team/therapists:

How do we ensure our child is independent, but has the support in class and at activities they need?

How can we adapt household items to help our child be independent?

How can Early Intervention (or other state funded programs) assist in the pre-school setting?

School age

Questions to ask medical team/therapists:

Will our child need support at school? Dressing, toileting, eating, carrying backpacks, supplies?

Do I need to write a note for their gym teacher?

How can we get an IEP or 504 plan for our child at our public school?

I’m planning on sending my child to private school, what are they required to adapt for my child?

Should my child participate in PE?

What/how can we speak with teachers and school staff about our child’s injury?

What is the ADA's role in a school?

How can we teach our child to advocate for themselves?

Options for modifications at school you may consider asking for

Rolling backpack

Second set of books to keep at home

Note-taker or recorder in class or notes provided

Apply sunblock from teacher/nurse when outside on injured arm (burns faster for some)

Assistance opening items at lunch (milk carton, containers)

Assistance carrying tray at lunch

Assistance toileting

Desk facing front of room and not sideways so child isn’t twisting and tiring out their upper body

Middle/Junior High/High School

Questions to ask medical team/therapists:

What types of accommodations/504 items will my child need as they get into the upper grades?

How can I ensure my child can participate in school or extracurricular teams fairly including sports?

Do I need to get a letter from their doctor/BP clinic about their injury to make sure they are not excluded due to their injury?

How can I help my child with their self confidence or body image?

How can I help my child learn to drive? What state requirements are there for this type of disability?

REMEMBER:

Your child is more than their injury. It is completely natural to have a wide range of emotional responses throughout your child's life as they age and meet some milestones, but not others. Anger, guilt, frustration are all too common for parents and families. Take time for yourself. Seek out counseling and find ways to connect with your child outside of “therapy time”. It is difficult not to compare your child to other “healthy/non-injured” babies and this is perhaps the hardest for parents. Your child will accomplish things you will not ever believe possible!

-

Brachial plexus birth injuries most often occur when an infant’s shoulder gets stuck behind the mother’s pelvic bone (called shoulder dystocia) and the force used in an attempt to pull the baby out is strong enough to damage the nerves near that shoulder. There are some known risk factors for brachial plexus birth injuries related to shoulder dystocia, but only about half of brachial plexus injuries had any of the known risk factors. Risks can be related to the physical size of the mother or baby, to the positioning of the mother during delivery, how the doctors assist the delivery, and more.

Along with known risk factors, there are known maneuvers (to help reposition the baby) and positions for the mother (specifically NOT flat on her back) that the healthcare provider can do to help put the baby into the right position to be delivered without injury. If both you and your provider are familiar with these maneuvers, the risk of brachial plexus injury decreases significantly.

Learning about these personally as well as making sure your healthcare providers have a good understanding of how to prevent brachial plexus birth injuries is critical, especially if you have had a baby with shoulder dystocia or brachial plexus birth injury before.

-

Risk factors in place before you even get pregnant (pre-pregnancy):

Maternal birth weight

Prior shoulder dystocia

Prior macrosomia (large baby)

Pre-existing diabetes

Obesity

Multiparity (a woman birthing her second child or who has had two or more children)

Prior gestational diabetes

Advanced maternal age

Short stature

Factors that present during pregnancy (antepartum)

Excessive maternal weight gain

Macrosomia

Postdatism (being over your due date)

Intrapartum(during birth):

Prolonged second stage

Protracted descent

Failure of descent of head

Abnormal first stage

Need for mid-pelvic or assisted delivery

Weight and Weight Gain

Weight and weight gain during pregnancy are critical factors during pregnancy. Mothers that weigh more than 81kg (~180 lbs) pre-pregnancy, experience 30% of all shoulder dystocias. In addition, more than a 20kg (44 lbs) pregnancy weight gain shows an increase in shoulder dystocia from 1.4% to 15.2%. This is an area that must be stressed by the OB/GYN during pre-pregnancy discussions and throughout the pregnancy. Screening for maternal diabetes must be the standard protocol, not an elected option.

For infants of non-diabetic mothers, the risk of shoulder dystocia is approximately 10 percent for infants weighing 4,000 to 4,499 grams (8.8-9.9 lbs)and 23 percent for infants >4,500 grams (9.9 lbs) . For infants of diabetic mothers the risk is 31 percent for infants >4,000 grams (8.8 lbs). Unfortunately, these statistics are only retrospective, since there is no adequate method for determining the accurate fetal weight.

Maternal weight gain, and the development of a macrosomic fetus are not the only predisposing factors.

Epidurals

The use of epidurals has been implicated to cause an increase in the incidence of cesarean sections for shoulder dystocias (10% vs. 3.8 % without epidurals). In addition, Stoddart et al., in a well-controlled randomized prospective study, showed that epidural anesthesia affects rotation of the shoulders because it relaxes the pelvic floor. Being in a recumbent position (lying down) has also been implicated in slowing down the baby's descent, prolonging the labor process, and potentially closing the birthing canal by up to 30%.

Positioning

Using the proper positioning during labor will help reduce the incidence of shoulder dystocia, by allowing the sacrum to move back freely and by allowing the birth canal to fully open. Thus, using the recumbent position (lying down) or semi-reclined position exacerbates the shoulder dystocia.

Borell and Fernstroms' (1957a) x-ray studies showed that the sacroiliac joint (part of the tailbone) moved during labor in relation to the descent of the fetus, and that these movements were not brought about by a change of maternal position at the particular time, but by the freedom of the joints to spread and open more.

In other words, the sacroiliac joints were free to move back as the baby passed through the birthing canal, because the women were not lying on their sacrum’s thus restricting such movement. They found that as the fetal head passes the pelvic inlet, i.e. at engagement, a movement of rotation occurs within the sacroiliac joint that increases the sagittal diameter of the pelvic inlet.

At the time the fetus passes the pelvic outlet, this movement of rotation is reversed, increasing the sagittal diameter of the pelvic outlet.

Basically, by keeping off her back (tailbone) the woman is giving her baby the widest possible opening for passage thus reducing the risks of trauma.

If a woman is sitting on her sacrum and sacroiliac joints during delivery, then there is an increased chance of precipitating a shoulder dystocia, and an increased likelihood of a brachial plexus injury.

Significantly closing the birth canal in the lying down or semi-reclined position, also increases the likelihood of a forceps or vacuum delivery, which in turn increases the risk of a brachial plexus injury and other birth trauma as well.

In an article from the Perinatal Institute, shoulder dystocia is discussed:

“Shoulder dystocia needs to be distinguished from a mere difficulty with delivery of the shoulder. The latter occurs because of the prevailing delivery practice, with the mother in a semi-recumbent position on the delivery bed. There may be insufficient room for appropriate lateral, i.e., downward flexion for delivering the anterior shoulder. In addition, the weight of the mother is in part taken on the sacrum that is therefore pushed upwards, thus decreasing the diameter of the pelvic outlet. Many of these cases require only a positional change, into left side lying, or kneeling, which frees the sacrum and allows lateral flexion”.

Information sources used in the preparation of this material: Shoulder Dystocia and Birth Injury: Prevention and Treatment by James. A. O’Leary, MD (McGraw-Hill, 1992); the informational website of Dr. O’Leary: www.shoulderdystocia.com; informational materials published by the Brachial Plexus Program at Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, TX; and the informational website of the Brachial Plexus Program at Texas Children’s Hospital which can be accessed through the main Texas Children’s Hospital website: www.texaschildrenshospital.org

-

Coming Soon…

ⓘ For Adults with BPI

Very little data regarding adults with brachial plexus birth injuries has been published in the medical literature, and what has been published can often appear to conflict. However, we have a lot of unofficial data that we have gathered from personal stories that can be found in our Facebook group.

Some commonly asked questions with general answers can also be found on the FAQ page.

Resources & Support

Join the United Brachial Plexus Network in making a difference! Whether you're seeking support, looking for information, or want to connect with others impacted by brachial plexus injuries, we’re here for you. Together, we can raise awareness, provide resources, and advocate for prevention and better care. Explore our network and be part of a global community dedicated to making life brighter for those affected by BPI.